Installation view

Galeria Centralis, Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives, Budapest, 13 March – 1 May 2016

Axel Braun: Video 01, Video 02, Img. 04

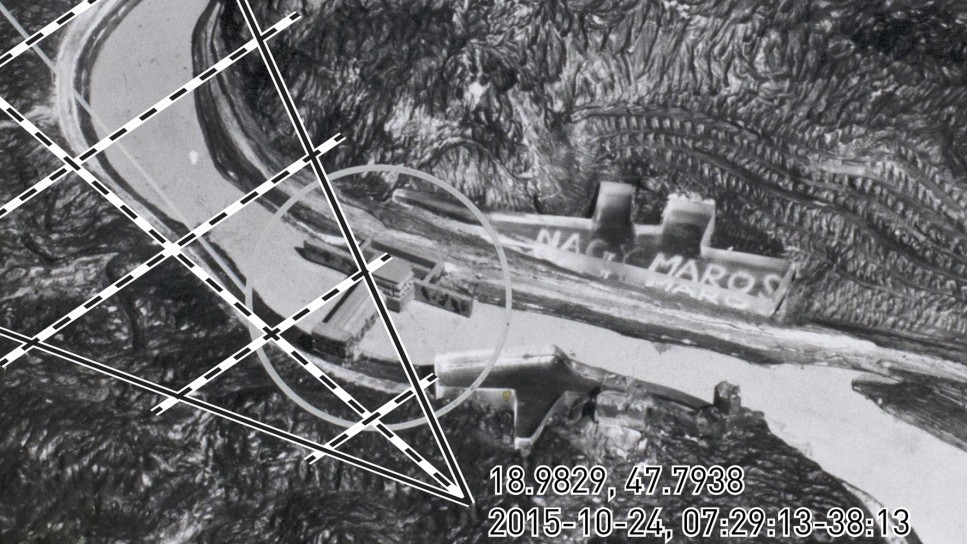

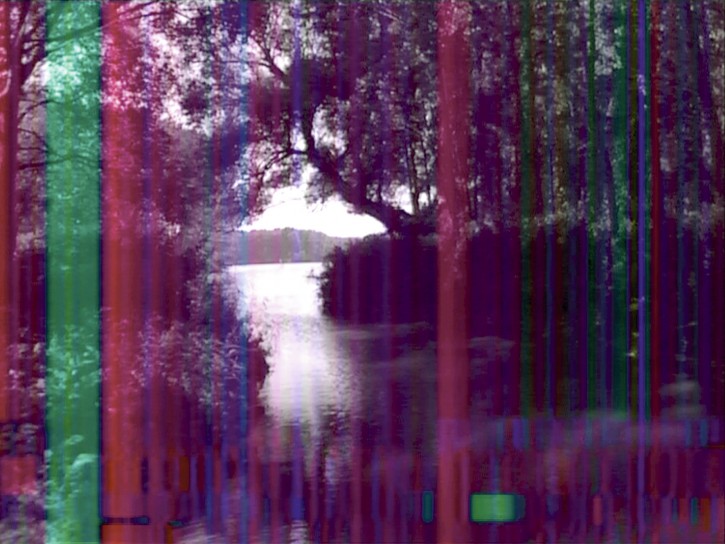

Video 01

Two views of the Danube Bend near Visegrad and Nagymaros

The Nagymaros dam was to be constructed in between the two settlements in order to compensate tidal waves caused by the Gabčíkovo power plant – more than 100 km upstream – that would have characterised the peak load operation mode of the Gabčíkovo power plant, as it was originally intented.

Axel Braun: Video 01, 2015, HD, 20’00”; walltext

Photo source: Környezetvédelmi és Vízügyi Levéltár Budapest

Video 01

Two views of the Danube Bend near Visegrad and Nagymaros

The Nagymaros dam was to be constructed in between the two settlements in order to compensate tidal waves caused by the Gabčíkovo power plant – more than 100 km upstream – that would have characterised the peak load operation mode of the Gabčíkovo power plant, as it was originally intented.

Axel Braun: Video 01, 2015, HD, 20’00”; walltext

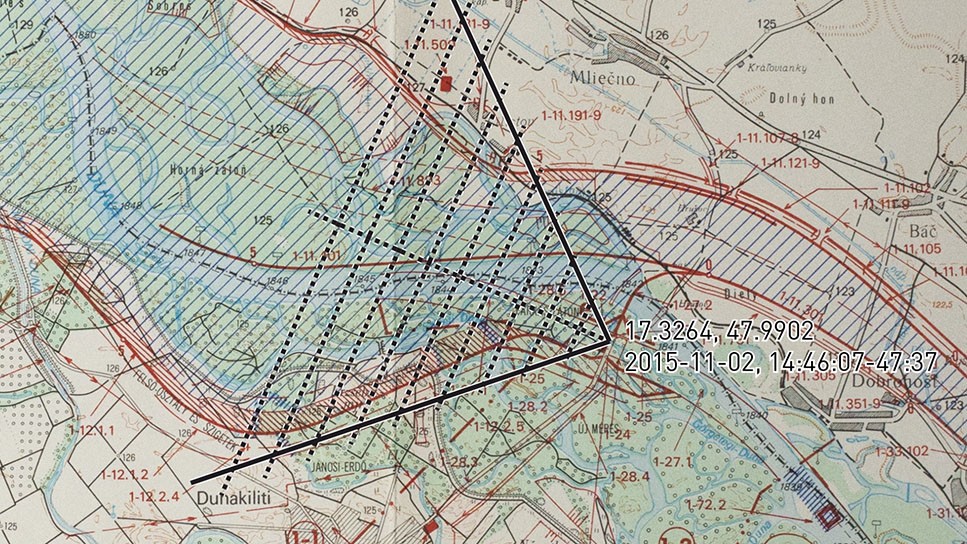

Zoom on scale model of the Nagymaros dam, angle, dates and coordinates visualise the camera position for the following take

Photo source: Környezetvédelmi és Vízügyi Levéltár Budapest

Video 01

Two views of the Danube Bend near Visegrad and Nagymaros

The Nagymaros dam was to be constructed in between the two settlements in order to compensate tidal waves caused by the Gabčíkovo power plant – more than 100 km upstream – that would have characterised the peak load operation mode of the Gabčíkovo power plant, as it was originally intented.

Axel Braun: Video 01, 2015, HD, 20’00”; walltext

Installation view

Axel Braun: Img. O1, Img. 02, Img. 03, Video 02; introductive texts

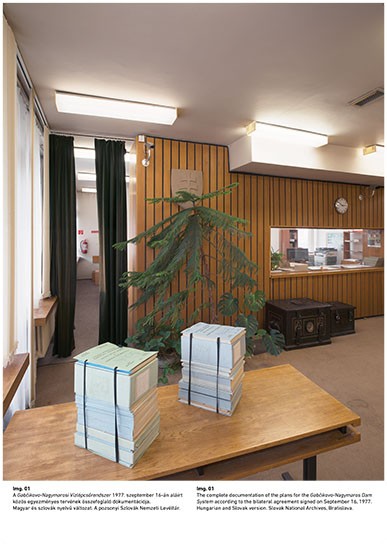

Img. 01

The complete documentation of the plans for the Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Dam System according to the bilateral agreement signed on September 16, 1977. Hungarian and Slovak version.

Slovak National Archives, Bratislava.

Axel Braun: Img. 01, Giclée Print on wallpaper, 59,4 cm x 84,1 cm, 2016

Img. 02

Decisions of the Hungarian Parliament in order to resign from the bilateral agreement to build the Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Dam System. Parliamentary Decisions 9/1989.(VI. 13) OGY; 24/1989.(XI. 10) OGY; 26/1991.(IV. 23) OGY; 12/1992.(IV. 4) OGY; Statement of the Government of the Republic of Hungary (October 23, 1992).

Hungarian National Archives, Budapest.

Axel Braun: Img. 02, Giclée Print on wallpaper, 59,4 cm x 84,1 cm, 2016

Img. 03

A deposit of concrete blocks on a former island at the Dunakiliti dam

The blocks were produced to build a gravity dam to redirect the Danube from its old riverbed into a canal towards the Gabčíkovo power plant, as it was intended in the original plans for the Gabčíkovo Nagymaros Dam System. The blocks remained on the island since the Hungarian government resigned from the bilateral agreement with Slovakia in 1991.

Axel Braun: Img. 03, wallpaper (Caspar Basic 465001), 250 cm x 200 cm, 2016; walltext

Installation view

Discourse Analysis (Protest) (Mediation) (System) (Landscape) (Contra) (Undecided) (Pro);

Video 02

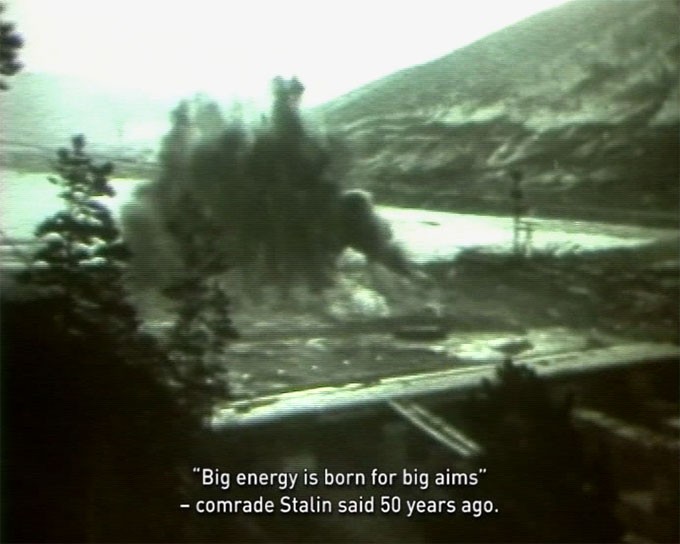

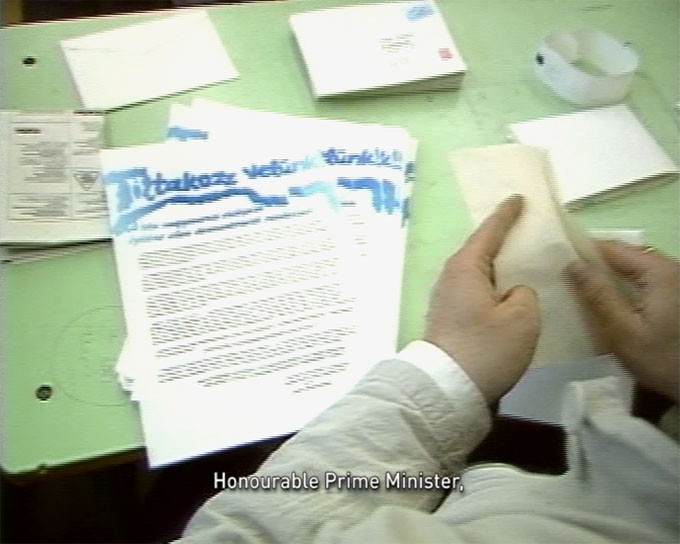

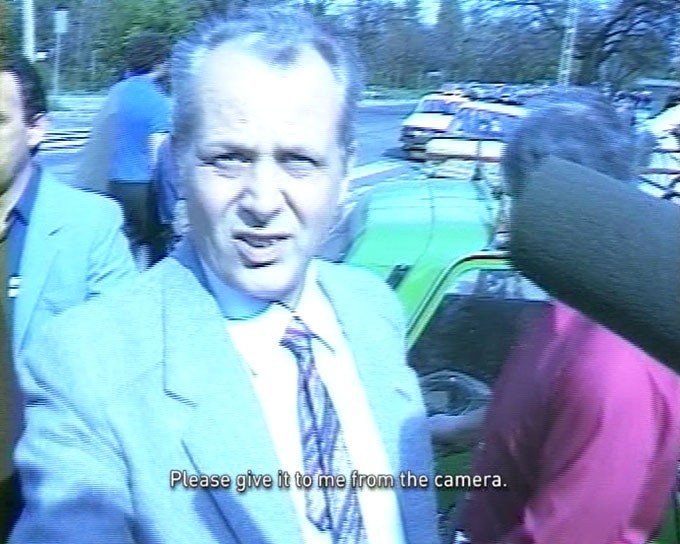

Discourse Analysis, re-edit of digitised BETA SP footage by Ádám Csillag and Fekete Doboz (1984-1992), still

Discourse Analysis (System), DVD, 26’55” (loop): excerpt of propaganda video about Stalin‘s hydro power projects; Ádám Csillag, “Dunaszaurusz” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (System): TV footage of György Lázár (Hungary) and Lubomír Štrougal (Czechoslovak Republic) signing the Mutual Construction and Operation Agreeement for the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System in Budapest, 1977; Ádám Csillag (1988)

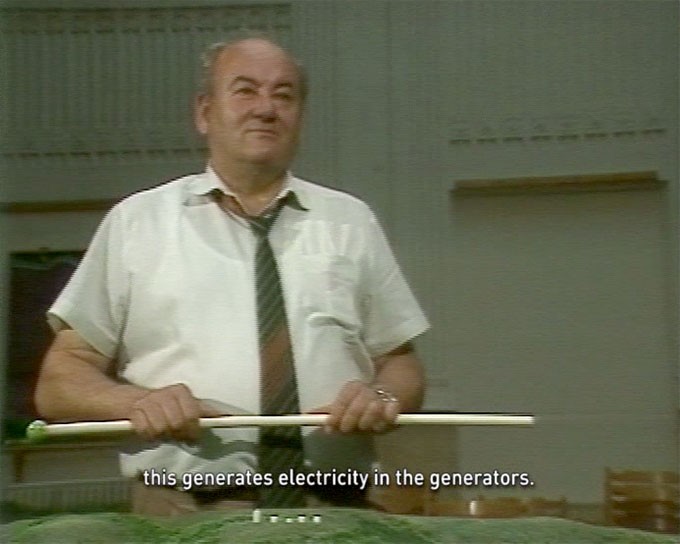

Discourse Analysis (Mediation), DVD, 3’54”: Miklós Szántó (Director of National Water Investment Company) explaining the functions of the Nagymaros dam at a scale model; Ádám Csillag, “Dunaszaurusz” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (Protest), DVD, 24’21” (loop): Members of Duna Kör preparing for a large protest action in Budapest on 23 May 1988; Ádám Csillag, “Dunaszaurusz” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (Protest): Activists handing out flyers during a protest in Budapest (undated); Fekete Doboz, “A Műtárgy” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (Protest), DVD, 24’21” (loop): Scenes of large protests against GNDS in Budapest in 1988 and 1989 organised by Duna Kör and FIDESZ (Young Democrats)

Installation view

Discourse Analysis (Protest), re-edit of digitised BETA SP footage by Ádám Csillag and Fekete Doboz (1984-1992)

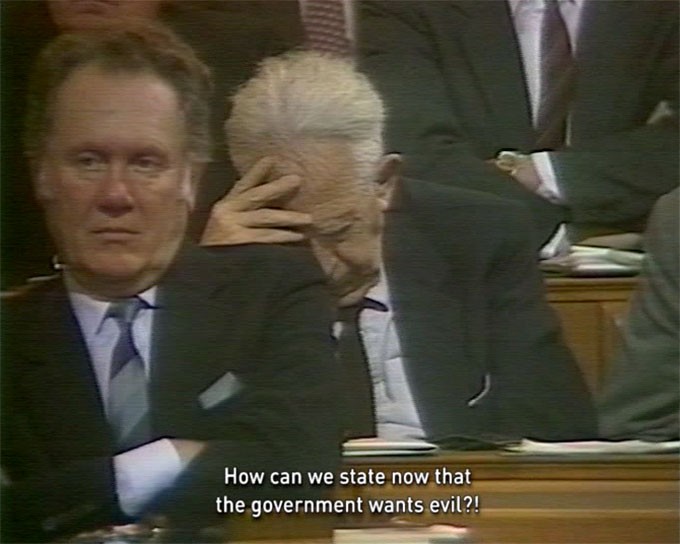

Discourse Analysis (System), DVD, 26’55” (loop): Plainclothes police officers confiscate recordings of Ádám Csillag’s camera team; Ádám Csillag, “Dunaszaurusz” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (System), Parliamentary Session (Budapest) on 7 October 1988, Gyula Varga (MP) reacting to a preceding speech of János Szentágothai (Director of Hungarian Academy of Sciences) that suggested to phase out from the GNDS project based on the results of the academy’s studies on the topic; Ádám Csillag, “Dunaszaurusz” (1988)

Discourse Analysis (Landscape), DVD, 6’23” (loop), still

Loop of digitised BETA SP footage by Ádám Csillag (c. 1992)

Already 20 years after recording the video tapes decompose, loose information on colour and bear numerous interferences

Installation view

Discourse Analysis (Contra) (Undecided) (Pro) (Landscape) (System) (Mediation); Video 02

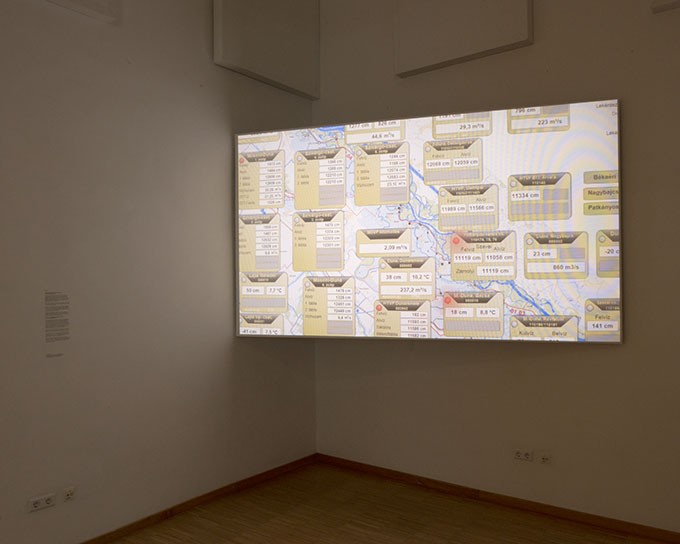

Video 02

Twelve views of the Gabčíkovo dam and related facilities

The scheme was almost finished in 1991 when the Hungarian government decided to resign from the bilateral agreement with Slovakia. While not building the dam had become a symbol for regime change and democratisation in Hungary, building the dam became symbol for energy autonomy and nation building in newly independent Slovakia. As no consensus between the two countries could be reached, Slovakia realised “varianta C” on her own by redirecting the Danube already at Čunovo, on Slovak territory, instead of Dunakiliti, where the Danube forms the border river between Hungary and Slovakia. Large parts of the Hungarian Szigetköz fell dry shortly after the redirection of the river in 1992, as the Slovak side channelled almost the entire current into the extended canal from Čunovo to Gabčíkovo.

Axel Braun: Video 02, 2014, HD, 21’00”; walltext

Video 02

Twelve views of the Gabčíkovo dam and related facilities

The scheme was almost finished in 1991 when the Hungarian government decided to resign from the bilateral agreement with Slovakia. While not building the dam had become a symbol for regime change and democratisation in Hungary, building the dam became symbol for energy autonomy and nation building in newly independent Slovakia. As no consensus between the two countries could be reached, Slovakia realised “varianta C” on her own by redirecting the Danube already at Čunovo, on Slovak territory, instead of Dunakiliti, where the Danube forms the border river between Hungary and Slovakia. Large parts of the Hungarian Szigetköz fell dry shortly after the redirection of the river in 1992, as the Slovak side channelled almost the entire current into the extended canal from Čunovo to Gabčíkovo.

Axel Braun: Video 02, 2014, HD, 21’00”; walltext

Installation view

Axel Braun: Video 03, 2015, HD, 12’00”; walltext

Video 03

The control room of Dunakiliti, a boat ride in the Szigetköz inland delta followed by views of the Dunakiliti dam

Centuries of land reclamation and agricultural development joined by regulations of the Danube for navigation purposes had taken away big parts of Europe’s last remaining inland delta before the constructions of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System began. Therefore a number of smaller weirs were built in the Szigetköz during the twentieth century in order to keep enough water in the delta that otherwise would run off too quickly to the dredged out main branch of the Old Danube.

Big parts of the delta fell dry after the redirection of the Danube at Čunovo in 1992, which caused an ecological disaster and eventually led to a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice.

As the Dunakiliti dam was almost finished when Hungary resigned from the bilateral contract with Slovakia, it became a central device to control the water flow in the Old Danube and in the Szigetköz, in order to reanimate and sustain the fragile ecosystem.

The whole hydrological system of the area – including the Old Danube, the Szigetköz, numerous irrigation canals and smaller side arms of the Danube – is coordinated from the Dunakiliti control room. The water management is executed in close cooperation with the Slovak run Čunovo dam.

Axel Braun: Video 03, 2015, HD, 12’00”; walltext

Video 03

The control room of Dunakiliti, a boat ride in the Szigetköz inland delta followed by views of the Dunakiliti dam

Centuries of land reclamation and agricultural development joined by regulations of the Danube for navigation purposes had taken away big parts of Europe’s last remaining inland delta before the constructions of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System began. Therefore a number of smaller weirs were built in the Szigetköz during the twentieth century in order to keep enough water in the delta that otherwise would run off too quickly to the dredged out main branch of the Old Danube.

Big parts of the delta fell dry after the redirection of the Danube at Čunovo in 1992, which caused an ecological disaster and eventually led to a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice.

As the Dunakiliti dam was almost finished when Hungary resigned from the bilateral contract with Slovakia, it became a central device to control the water flow in the Old Danube and in the Szigetköz, in order to reanimate and sustain the fragile ecosystem.

The whole hydrological system of the area – including the Old Danube, the Szigetköz, numerous irrigation canals and smaller side arms of the Danube – is coordinated from the Dunakiliti control room. The water management is executed in close cooperation with the Slovak run Čunovo dam.

Axel Braun: Video 03, 2015, HD, 12’00”; walltext

Video 03

The control room of Dunakiliti, a boat ride in the Szigetköz inland delta followed by views of the Dunakiliti dam

Centuries of land reclamation and agricultural development joined by regulations of the Danube for navigation purposes had taken away big parts of Europe’s last remaining inland delta before the constructions of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System began. Therefore a number of smaller weirs were built in the Szigetköz during the twentieth century in order to keep enough water in the delta that otherwise would run off too quickly to the dredged out main branch of the Old Danube.

Big parts of the delta fell dry after the redirection of the Danube at Čunovo in 1992, which caused an ecological disaster and eventually led to a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice.

As the Dunakiliti dam was almost finished when Hungary resigned from the bilateral contract with Slovakia, it became a central device to control the water flow in the Old Danube and in the Szigetköz, in order to reanimate and sustain the fragile ecosystem.

The whole hydrological system of the area – including the Old Danube, the Szigetköz, numerous irrigation canals and smaller side arms of the Danube – is coordinated from the Dunakiliti control room. The water management is executed in close cooperation with the Slovak run Čunovo dam.

Axel Braun: Video 03, 2015, HD, 12’00”; walltext

Video 03

The control room of Dunakiliti, a boat ride in the Szigetköz inland delta followed by views of the Dunakiliti dam

Centuries of land reclamation and agricultural development joined by regulations of the Danube for navigation purposes had taken away big parts of Europe’s last remaining inland delta before the constructions of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Dam System began. Therefore a number of smaller weirs were built in the Szigetköz during the twentieth century in order to keep enough water in the delta that otherwise would run off too quickly to the dredged out main branch of the Old Danube.

Big parts of the delta fell dry after the redirection of the Danube at Čunovo in 1992, which caused an ecological disaster and eventually led to a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice.

As the Dunakiliti dam was almost finished when Hungary resigned from the bilateral contract with Slovakia, it became a central device to control the water flow in the Old Danube and in the Szigetköz, in order to reanimate and sustain the fragile ecosystem.

The whole hydrological system of the area – including the Old Danube, the Szigetköz, numerous irrigation canals and smaller side arms of the Danube – is coordinated from the Dunakiliti control room. The water management is executed in close cooperation with the Slovak run Čunovo dam.

Axel Braun: Video 03, 2015, HD, 12’00”; walltext

Installation view

Archival References, Img. 04, Video 04, Video 01,

Img. 04

A side arm of the Danube in the Szigetköz inland delta

Beavers chewed off the trees that fell into the water. The mammal was completely extinct in the 1990s when ten couples were resettled in the delta. Meanwhile the beaver population is estimated to up to 1000 animals, as they have no natural enemies.

It has been considered to decimate their number by hunters, as their activity becomes a threat for the maintenance of the deltas banks that are particularly exposed to erosion.

Axel Braun: Img. 04, wallpaper (Caspar Basic 465001), 300 cm x 200 cm, 2016; walltext

*Archival References II, detail

Flyers, stickers and protest invitations for anti-GNDS actions, photo documents of protest in Budapest (1988)

Img. 05

An oxbow in Szigetköz that recently dried out

Due to the diversion of the Danube at Čunovo the ground water level in the Szigetköz fell about 10 metres. Thus not all parts of the delta can be irrigated permanently. The engineers at Dunakiliti aim for a restoration of the average water level of the 1970s, while simulating seasonal floods and dry periods, as they would occur naturally.

Axel Braun: Img. 05, wallpaper (Caspar Basic 465001), 352 x 200 cm, 2016; walltext

Ádám Csillag: International Court of Justice – Case Concerning the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Project (1997)

Ádám Csillag documented all court sessions in The Hague from 1997 to 1998, meanwhile some of his recordings were damaged or lost; Axel Braun digitised the remaining BETA SP tapes and compiled a loop (DV, 387’22”)

Installation view

Archival References, Img. 05, International Court of Justice

Archival References III, detail

Photo documentation of construction works at Dunakiliti / Rajka (1981-1988) and Nagymaros (1988)

Archival References, Img. 04

Photo: Dániel Végél

Video 04

View of the Water Sports Centre and the Danubiana Gallery on Čunovo dam

When Hungary resigned from the bilateral contract in 1991, Slovakia completed “varianta C” on her own. The Danube forms the border river between the two countries from Dunakiliti for more than 100 km, but at Čunovo both river banks lie on Slovak

territory. As the original plan to divert the Danube at Dunakiliti was not realisable anymore, the Slovak government decided to build a longer canal than originally planned, from Čunovo to Gabčíkovo, in order to bypass Hungarian objections.

The Čunovo dam and reservoir became popular sites for sports and cultural activities.

Axel Braun: Video 04, 2015, HD, 7’00”; walltext

Axel Braun: Video 04, 2015, HD, 7’00”; walltext

Video 01

Two views of the Danube Bend near Visegrad and Nagymaros

The Nagymaros dam was to be constructed in between the two settlements in order to compensate tidal waves caused by the Gabčíkovo power plant – more than 100 km upstream – that would have characterised the peak load operation mode of the Gabčíkovo power plant, as it was originally intented.

Axel Braun: Video 01, 2015, HD, 20’00”; walltext

Installation view

Video 01 and auditorium

Installation as stage for collateral events

Ádám Krasz Music for Flute and Electronics, 28 April 2015; Photo: Horváth Szabolcs

Installation view

Reading table with photocopies of multipage texts shown in the vitrines to make the Archival References fully accessible for the visitors; further literature on Duna Kör, the GNDS controversy as well as the context of Axel Braun‘s Towards an Understanding of

Anthropocene Landscapes, art in context of environmental issues and a recording of a roundtable discussion about GNDS (1988)